Twenty years ago, if you found yourself standing next to the volatile, gravity-defying Alva at some crowded backyard pool in the Valley, and he wasplanning to take the next run--even though he'd just taken the last one--it was best to not even look at him.

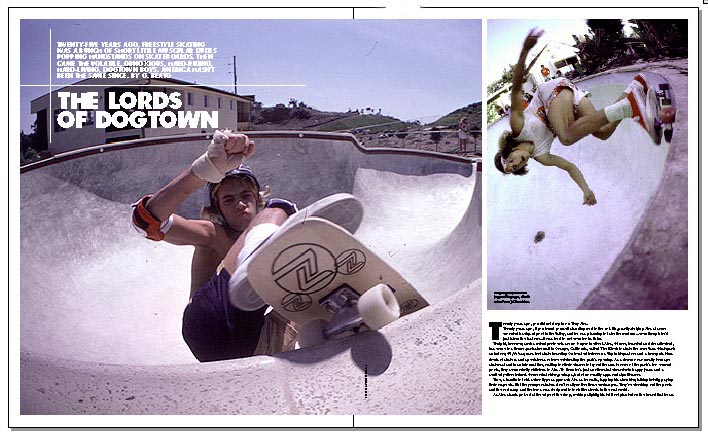

Tonight, however, such ancient protocols are no longer in effect. Alva, 41 now, bearded and dreadlocked, has come to The Block, a theme park?size mall in Orange, California, to skate the new Vans Skatepark, an indoor, 46,000-square- foot skateboarding Oz located between a Virgin Megastore and a brewpub. Hundreds of skaters and spectators are here celebrating the park's opening. As a dozen or so mostly teenage skaters stand in an informal line, waiting for their chance to try out the smaller one of the park's two cement pools, they seem wholly oblivious to Alva. To them he's just another skateboarder in baggy jeans and a scuffed yellow helmet. Somewhat older, perhaps, but of no readily apparent significance.

True, a handful of old-school types approach Alva as he waits, tapping his shoulder, talking briefly, paying their respects. But the younger skaters don't really notice these exchanges. They're checking out the pools and the vert ramp and the two areas designed to look like streets in the real world.

As Alva stands poised at the edge of the drop, rocking slightly, his left foot planted on the board that bears his name, a wispy blond-haired nine-year-old, completely unaware of him, stands in the same position just a few feet away. And when the guy in the pool blows a backside grind at its far end, the nine- year-old pushes off with his right foot.

It's a moment of minor blasphemy--a nine-year-old, a kid who can barely even skate, dropping in on Alva! Alva, the leader of the Dogtown boys, the former World Champion, the godfather of urban skate-punks who transformed skateboarding from a sport of short little muscular dudes doing nose wheelies into the minor religion that it is today. Does the kid have any clue what he's doing? Any clue at all?

Twenty years ago, "Mad Dog" Alva would have fired his board at the tiny kid's head. But today, he simply claps twice, like a Little League coach, and smiles at all the shorties in line.

"HEY, IS THIS YOUR CARBURETOR?" Tony Alva grew up in Santa Monica, a few blocks from the beach and a failed amusement park called Pacific Ocean Park. In 1958, CBS spent $10 million renovating the 28-acre park, which was built on a huge concrete-and-steel pier. By 1967, however, the park had been shut down due to poor attendance and soon fell into a state of slow deterioration.

While much of the original SoCal surf culture sprang up around affluent enclaves like Malibu and La Jolla, the Venice/Santa Monica area that Pacific Ocean Park bridged was run-down and gritty. Dogtown, the locals called it. The streets were lined with boarded-up storefronts, liquor stores, and ratty dives, like an underground coke-snorting emporium known as the Mirror-Go- Round. The area beneath the pier was even seedier. Junkies shot up there, gay men used it as an anonymous trysting spot, bums established long-term subterranean encampments. But the pier served another function as well: 275 feet wide, extending hundreds of feet into the ocean, it created three separate breaks for the Dogtown locals to surf.

The danger inherent in surfing the P.O.P. pier, with its numerous concrete pilings and crowded conditions, led to a tradition of intense clannishness: You had to have confidence in your fellow surfers. Sometimes outsiders were discouraged via an abrupt punch in the face, no questions asked. On other occasions, a local might paddle out to an alien surfer, clutching a carburetor in his free hand. "Is this yours?" he would ask the trespasser, then drop the carburetor into the ocean. It was here, in P.O.P. surf culture, that Alva was introduced to the principles that would later inform the Dogtown skate scene.

The same year that Pacific Ocean Park closed, Alva's mother divorced his father. Alva's sister and brother went with their mom; nine-year-old Tony remained with his dad. "My dad worked a lot, so I didn't really see him that much," says Alva. And while his father coached him in Little League and bought him his first surfboard at the age of ten, there was also a darker side to their relationship. "He was angry at a lot of different things," Alva recalls. "When he drank, he could be kind of brutal."

As a consequence, Alva spent as much time as possible at the beach, where he used to hang with another local kid named Jay Adams. Four years younger than Alva, Adams had practically grown up on the beach. His stepdad was a surfer who owned a rental concession on the pier's northside, and Adams was always underfoot, a skinny, hyperactive board-sports prodigy with a malicious grin and a spontaneous approach to life--Huck Finn by way of the Pacific Coast Highway. He started surfing almost as soon as he had learned to swim; by the time he was eight, he was already an accomplished surfer and a fixture at P.O.P.

Me and Jay were like the only younger kids allowed to surf there," says Alva. "But we had to earn it first. The older guys would go, 'Okay, you can come out for a while, but first you have to do Rat Patrol.' We'd sit up on the pier with these wrist rockets and this pile of polished stones, and just bombard anyone who was from outside our territory with whatever was available. Rocks, bottles, rotten fruit. Jay was a notoriously good shot."

PAUL REVERE'S WILD RIDE In 1970, Alva and a couple of friends decided to ride their bikes to Brentwood to check out Paul Revere Junior High. Some of the older P.O.P. surfers had been talking about the school's playground. Revere was built on a hillside, and for whatever reasons of economy or aesthetics, the flat playground was edged with sharply sloping, 15-foot-high banks instead of retaining walls. "To a 12-year-old kid it was awesome," Alva says. "The asphalt had just been repaved, so the banks were really smooth and pristine--just these huge, glassy waves."

Throughout the '60s, surfing had always taken precedence over skateboarding in Dogtown. Skating was mostly just a means of transportation, or something to do if the waves weren't breaking. By 1970, the sport had reached a particularly desultory stage. "No one was skateboarding back then. You couldn't even buy a skateboard in the store," says Stacy Peralta, another Dogtown local. Kids would often have to construct their own from spare pieces of household furniture and repurposed roller skate parts.

But after the Dogtown kids discovered Paul Revere and other schoolyard skate spots like Bellagio and Kenter Canyon, the inadequacies of their equipment seemed incidental. The schoolyards' asphalt "waves" broke beautifully every single day, all year round, creating entirely new possibilities for the sport. The Dogtown kids started applying their surfing techniques to concrete, riding low to the ground with their arms outstretched for balance, skating with such intensity that they often destroyed their homemade boards in a single session.

"We were just trying to emulate our favorite Australian surfers," Alva says, explaining the genesis of their new low-slung, super-aggressive style. "They were doing all this crazy stuff that we were still trying to figure out in the water--but on skateboards, we could do it."

Three years later, the introduction of urethane wheels resurrected interest in skateboarding. By then, the Dogtown kids had developed an approach to skating that was far more evolved than what anyone was doing at the time. "No one else had that same surf-skate style, because they didn't have banks like that anywhere else," Alva says. "We had this tradition that was unique to our area."

THE IMPORTANCE OF CUSTOMER SERVICE Outside the Jeff Ho & Zephyr Productions Surf Shop, in front of a wall-size mural of co-owner Jeff Ho surfing a wave that was almost pornographic in its perfect, arcing glassiness, Alva and Adams and a few other Dogtown kids were skateboarding back and forth, cutting off cars, catcalling passing girls, staring down all the pedestrians who failed to avoid them--like the two guys who had just rolled in from Van Nuys or wherever, more jock than surfer (but trying hard with their Vans and Hang Ten shirts), who tried to enter the shop's front door. It was locked. They looked at their watches. It was 3 p.m.

Inside, Skip Engblom, one of the shop's owners, sat in a rocking chair,

drinking vodka and papaya juice and watching the scene play out. This

was one

of his favorite pastimes.

"Hey!" cried one of the Van Nuys guys, finally noticing him. "Open up.

This

door's locked."

"What the fuck do you want?" Engblom yelled back.

"I want to look around."

"If you want to come in here, you've got to give me some money first,"

Engblom

said. "If you just want to look around, go to the fucking library."

"I've got fucking money," the guy said, pulling a twenty out of his

wallet and

waving it in front of the window. "Let me in and I'll spend it!"

It was an innovative approach to customer service, characteristic of Ho

and

Engblom's general approach to commerce. The pair had formed their

partnership

in 1968, when both men were still in their late teens. Ho was a gypsy

surfboard shaper living in the back of his '48 Chevy panel truck;

Engblom was

a vagabond surfer who'd been traveling around the world in an effort to

avoid

the draft.

Their goal was to be a completely self-contained entity, reliant on no one. To this end, they designed, manufactured, and sold their own surfboards; they created their own clothing line; they produced their own advertising and promotional movies. Sometimes, however, they would sell other people's merchandise. "We did a lot of stuff that would be considered illegal," allows Engblom. Various wholesalers sold them an impressive array of surfing lifestyle accessories, like 15,000 Quaaludes or vast amounts of fireworks. "Once, we ended up buying a quarter of a barge of firecrackers," says Engblom. "We didn't know how much that was exactly. But the price sounded really cheap."

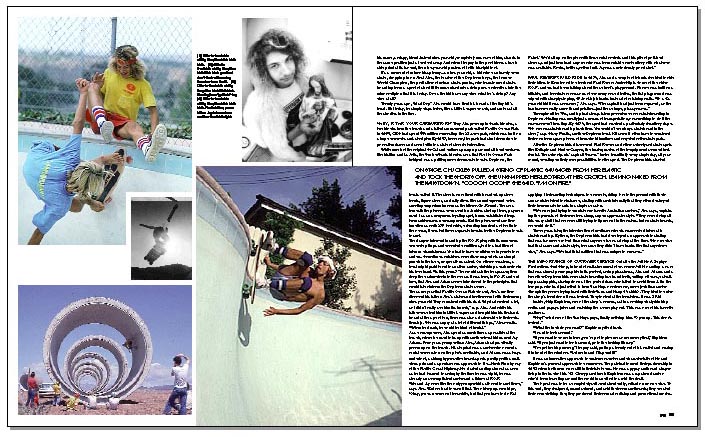

For the local Dogtown kids, the shop served as a second home. They used to help Ho shape and repair boards in the shop's backrooms in exchange for discounts or free merchandise. At night, the place turned into a kind of speakeasy, over which the charismatic Ho--wearing rainbow-tinted glasses, four-inch platform shoes, and striped velveteen pants--presided. Local bands performed, and drugs were dispensed with typical '70s largesse.

With his shop, Ho tried to provide the same sense of family and community that he'd found at the beach as a kid growing up. "I was a loner, this geeky little Chinese runt kid who couldn't play sports until I discovered surfing. And then I saw these other kids, growing up the same way. I mean, who's going to be hanging out all day at the beach? The kids who don't want to be hanging out at home. So, to them, I would say, 'Check it out, this is surfing. If you use your talents, you can make something of yourself.'"

To this end, Ho sponsored two surf teams: one for the area's best surfers, guys who were in their late teens and early 20s, and, in a move that was fairly unusual at the time, one for the younger kids, who were destined to become the next wave of stars. As skateboarding's popularity increased, the junior surf team, which had included Tony Alva, Jay Adams, Shogo Kubo, and Stacy Peralta, evolved into the Zephyr Competition Skate Team--a 12-member group of the best skaters in Dogtown. Ho gave them team T-shirts. "We wanted to give them colors, something to be a part of."

"To wear the team shirt was just unreal," says Peralta. "We were all middle- and lower-class kids, and it wasn't like we had a lot of opportunities. We weren't the kids who were going to graduate as valedictorians or the guys from Palisades driving BMWs to the beach. So to be chosen to be a part of something like that was just the hottest thing that could happen to a kid in that area."

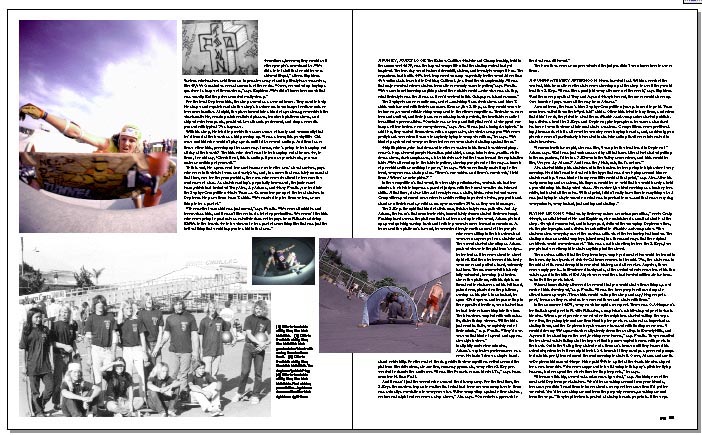

The Zephyr team wore uniforms, sort of--matching Vans deck shoes and blue T- shirts emblazoned with their team name. Even so, the Z-Boys, as they would come to be known, seemed wild-looking compared to the other competitors. Their shoes were torn and scuffed, and their jeans were missing back pockets, the inevitable result of low-altitude power-slides. "Our hair was so long and fluffy that we'd all chopped our bangs off two inches over our eyebrows," says Alva. "It was just a funky, funky look." In addition, they carried themselves with an aggressive, streetwise swagger. "We were pretty hard-core when it came to anybody trying to compete with us," he says. "We kind of psyched out everyone there before we even started skating against them."

Skip Engblom, who had dressed for the occasion in his finest beachfront pimp- wear (a long-sleeved purple Hawaiian-print shirt, a snap-brim fedora, vanilla- white dress shoes, dark sunglasses, a black briefcase), led the team toward the registration table. "We all went up to the table together, shoving people out of the way--a bunch of poor kids with something to prove," he says. "When we finally made it up to the front, everyone was staring at us. 'There's our entries and there's our check,' I told them. 'Where's our trophies?'"

In the competition's first event, the freestyle preliminaries, contestants had two minutes in which to impress a panel of judges with their most creative skateboard skills. At that time, state-of-the-art freestyle was a static, tricks-oriented endeavor: Competitors performed nose wheelies while rolling in perfect circles, popped handstands on their boards, or did as many consecutive 360s as they could manage.

The Z-Boys thought that kind of stick-man, tick-tack style was pathetic. And Jay Adams, the team's first member to ride, immediately demonstrated their contempt. Pushing hard across the platform that had been set up for the event, Adams picked up speed quickly, carving back and forth to generate more forward momentum. As he neared the platform's far end, he crouched low, lower than most of the people who were sitting in the bleachers had ever seen anyone get on a skateboard.

The crowd started shouting as Adams pushed closer to the platform's edge--he looked as if he were about to shoot right off. But then he lowered his body even more and pulled a hard, extremely fast turn. The maneuver left his body fully extended, hovering just inches above the platform, with his right arm thrust out for balance and his left hand, palm down, planted on the platform, serving as his pivot. In an instant, he spun 180 degrees and began rolling in the opposite direction, even faster than he was before launching into the turn. The bleachers erupted with enthusiastic, disbelieving cheers. "All the kids just went ballistic, completely out of their minds," says Peralta. "They'd never seen that kind of speed and aggressive style before."

In slightly under two minutes, Adams's explosive performance was over. He hadn't done a single handstand or kickflip. For the rest of the day, while their competitors rolled around the platform like ridiculous, slo-motion, runaway gymnasts, every other Z-Boy proceeded to dazzle the audience. "It was like Ferraris versus Model-T's," says team member Nathan Pratt.

And it wasn't just the crowd that sensed the discrepancy. For the first time, the Z-Boys themselves began to realize that what had become commonplace to them was actually a revelation to everyone else. "After competing against other skaters, we knew straight out we were a step above," Alva says. "Our whole approach to the deal was different."

The Zephyr team's routines were so unprecedented the judges didn't even know how to score them.

A GUNFIGHT EVERY AFTERNOON News traveled fast. Within a week of the contest, kids from all over the state were showing up at the shop to see if they could best the Z-Boys. "It was like a gunfight every afternoon of the week," says Engblom. "And the more guys that Tony and Jay and Stacy blew out, the more would show up. One bunch of guys came all the way from Arizona."

Around town, the team's blue Zephyr Competition jerseys turned to gold. Team members called them their "get-laid" shirts. Other kids tried to buy them, and when that didn't work, they tried to steal them. Skateboarder magazine started publishing articles about the Z-Boys and Dogtown; photographers became a standard feature of even their most informal skate sessions. Competitions were proliferating, thousands of kids all over the country were buying boards, and suddenly people who weren't particularly interested in skateboarding itself were interested in skateboarders.

"I remember this one girl, she was like, 'I can give the best head in Dogtown!'" Adams says. "But I was just embarrassed by all that fame. Like after I started getting in the magazines, I'd be in a 7-Eleven in the Valley somewhere, and kids would be like, 'Are you Jay Adams?' And I was like, 'Nah, nah, that's not me.'"

Alva started hiding his skateboard in the bushes before going to high school every morning. He didn't want to deal with the hype that was developing around him or skateboarding. "I was kind of in my own little world at that point," says Alva. After his early-morning surf sessions, his fingers would be so cold that he could barely hold a pencil during his first-period class. After school, he tried working as a busboy for a while, but hated all the rules. "At that point, I didn't really have time for anything else. I was just trying to stay focused on what was important to me--and that was every day, every minute, every instant, just surfing and skating."

FLYING LESSONS "Skaters by their very nature are urban guerrillas," wrote Craig Stecyk, an artist friend of Ho and Engblom's, who maintained a small art studio at the shop. Stecyk documented and, in large part, defined the emerging Dogtown ethos via the photographs and articles he submitted to Skateboarder magazine. "The skater makes everyday use of the useless artifacts of the technological burden. The skating urban anarchist employs [structures] in a thousand ways that the original architects could never dream of." This was a radical notion: Before the Z-Boys, few people had ever thought to skate anything but pavement. The useless artifact that the Dogtown boys employed most often could be found in the bone-dry backyards of rich SoCal homeowners. In the mid-'70s, the state was in the midst of one of its worst droughts in recorded history, and all over Los Angeles, there were empty pools--in Brentwood backyards, at the secluded outer reaches of Malibu estates, and in the hills of Bel Air, where recent fires had leveled million-dollar houses but left the pools intact.

"Almost immediately after we discovered that you could skate these things, a network of kids developed," says Peralta. "It was like how people will use drugs to attract famous people. These kids would call up the shop and say, �Hey, we got a pool,' because they wanted us to come out there and skate with them."

In the summer of 1976, every week brought a new pool. There was O.J. Simpson's football-shaped pool in Pacific Palisades, a magician's rabbit shaped pool in Santa Monica. When a pool grew too crowded or the neighbors started calling the cops too often, they simply found another. Hunting for pools was almost as important as skating them, and the Dogtown boys became obsessed with finding new ones.

"I would drive my VW squareback really slowly down these alleys in Beverly Hills, and Jay would be standing on the roof, looking over fences," says Peralta. They consulted the local real estate listings in the hope of finding unoccupied homes with pools in the back. Out in the Valley, they staked out a fireman's house until they learned his schedule; when he left one night for his 24-hour shift they used gas-powered pumps to drain his pool, then returned the next morning to skate it. Once, Adams and Shogo Kubo paid $40 to a pilot at the Santa Monica airport for a one-hour ride. "You were supposed to be listening to this guy's pitch for flying lessons, but we spent the whole time looking for pools," he says.

"It became this big, secret, cat-and-mouse-type deal," says Jim Muir, one of the most avid Dogtown pool-skaters. "You'd be sneaking around from your friends, because you didn't want them to know about a new pool because then it'd get too crowded. You'd be sneaking around from the property owners, sneaking around from the cops." They kept lookouts posted at strategic vantage points. If the cops rolled up in front of the house, they simply ran out the back. If the cops came from the back as well, then the Dogtowners went sideways, over fences. Soon, as many as four or five police cars were responding to calls. "The one place where we did get harassed constantly was this abandoned estate in Santa Monica Canyon across the street from [Mission Impossible star] Peter Graves's place," says Peralta. "He'd call the cops on us and we'd climb up into the trees and hide--and they'd be right below us, searching, not seeing us while we were up there. As soon as they left, we'd climb down and start skating again."

When the cops did catch them, they were usually let off with a warning. On occasion, they were arrested for trespassing. That only made them more determined. "The adrenaline rush of jumping over a fence and actually skating in someone's backyard and getting out of there before they came home--that was totally crazy," Alva says. "You can't jump over people's fences in Beverly Hills nowadays. You'd get eaten by a Doberman, shot by a security guy."

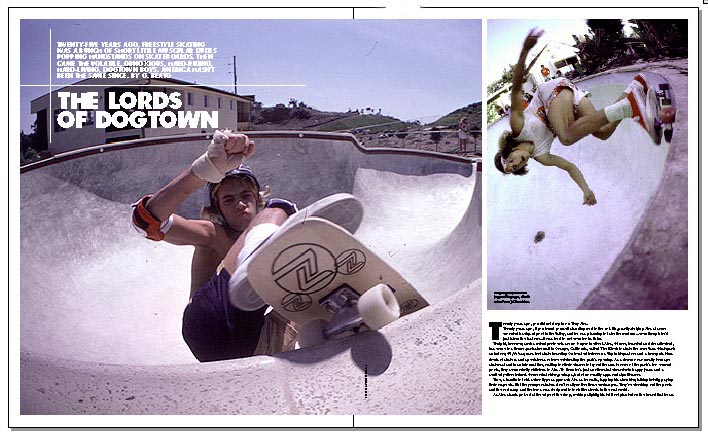

Like the schoolyard banks, pools offered a controlled vertical environment that led to rapid innovation; most skateboarders believe that Dogtown is the birthplace of aerials (others claim it was San Diego). "Aerials came from surviving, from being very aggressive and hitting the lip until eventually we were just popping out and grabbing the board in the air," says Alva. "It was something instinctive. Either you made it or you ended up on the bottom of pool, a bloody mess. It happened by total spontaneous combustion. Then we realized that there was an endless array of things we could do."

Photographers like Stecyk and Glen E. Friedman (who was 13 at the time) started capturing these revolutionary moves on film. Suddenly, all across America, kids were ripping out the pages of Skateboarder magazine and hanging photos of the Dogtowners on their walls: Tony Alva, flipping off the camera while hanging sideways in mid-air; Jay Adams, his face twisted into a look of the most primal juvenile-delinquent disdain, grinding the edge of a pool so hard he actually knocks its coping out of place.

"Rebels have always been popular--but really obnoxious, fucked-up rebels?" asks Friedman, assessing the appeal of these overnight teenage icons. "When girls used to ask Jay for his autograph, he'd draw swastikas on their breasts. He wasn't a Nazi, he just did it to be fucked-up. What the Sex Pistols started doing in 1976, Jay and Tony were doing a year earlier."

Complicating matters were the shop's own growing pains. Ho and Engblom had entered into a partnership with Jay Adams's stepfather, Kent Sherwood, to produce a line of Zephyr-Flex fiberglass skateboards, and the new partners began to have disagreements. "Basically, Kent decided we weren't selling the boards fast enough, so things got kind of weird and crazy," says Ho. "Selling skateboards fucked things up."

"We were still basically kids ourselves," says Engblom. "But all the sudden we were getting orders for 10,000 skateboards, and it was like, 'How do we produce this?'"

Ultimately, Sherwood ended his partnership with the pair and started his own company called Z-Flex. As a consequence, Adams and several others team members left Zephyr and began riding for the new company.

In the aftermath of that exodus, Ho began trying to put together a sponsorship deal that would keep the rest of the team together, but he wasn't able to pull it off. Alva left for Logan Earth Ski; Peralta signed a deal with Gordon & Smith. "I tried to get them to see the value of starting as a unit, and ending as a unit," says Ho. "But everyone had decided that they wanted to make their millions."

INTRODUCING TONY BLUETILE One day, the Dogtown boys were sneaking into movie star pools; the next, they were appearing in movies. Tony Alva landed a role in the film Skateboard as "Tony Bluetile," a farting, beer-drinking, Playboy- reading skate-thug who ends up losing the big race to Leif Garrett. Stacy Peralta, who at 17 was suddenly earning $5,000 a month from his sponsorship deal with G & S, starred in Freewheelin', a low-budget, cheesy skateboarder romance released in 1976. "I was so embarrassed at the premiere," says Peralta, "that I hid behind a curtain the whole time."

While the executive director of the International Skateboard Association primly told People magazine that Tony Alva represented "everything that is vile in the sport," the new Dogtown style was in high demand all across the country. For kids who couldn't quite match Alva's radical athleticism or Jay Adams's spontaneous irreverence, a skateboard or helmet bearing their signatures was the next best thing.

But could you really package the ungovernable energy of a guy like Jay Adams? Could you really turn a kid who barreled down the streets of West Los Angeles plucking wigs from the heads of old ladies into your corporate spokesdude? Often you couldn't. In Mexico, where Adams, Alva, and several other Dogtowners had traveled to attend the opening of a new skatepark, the kids who had once emulated their favorite Australian surf heroes now began to resemble rock stars.

"When we got there, this guy told us that if we wanted to score any pot or anything, that they would set us up," says Alva. "It ended up being the cops who brought it to us, this big trash bag full of weed." In the daytime they skated, and at night they partied with groupies and trashed their hotel rooms. At a local brothel, a fat, lactating prostitute ardently pursued the 16-year- old Adams. "She just kept chasing him around the room, shooting milk out of her tits at him," says Alva. "We were these full-on little rats in surf trunks who got wild and raised hell, and [skate promoters] just fed off our energy. It was almost like being on tour with Metallica."

As Alva's notoriety increased, he started hanging out with rock stars and wearing white suits and wide-brimmed, pimp-style fedoras. When he and his new friend Bunker Spreckels, a playboy millionaire heir to a sugar fortune and the stepson of Clark Gable, went in search of new pools to skate in Beverly Hills, they hired limousines to chauffeur them.

By 1977, all of the Dogtown boys were prospering. Alva won the World Pro Championship that year. Soon after, he left Logan Earth Ski, and, with the help of an entrepreneur named Pete Zehnder, created his own line of skateboards. (The company's slogan: "No matter how big your ego, my boards will blow your mind.") Peralta left his sponsor to become a partner in Powell Skateboards, which subsequently became known as Powell-Peralta. Jim Muir and another Dogtown local, Wes Humpston--who used to draw on his homemade boards to pass the time while traveling to various skate spots--trademarked the Dogtown name and produced the first line of skateboards to feature elaborate graphics on the underside of their decks. Jay Adams had his signature Z-Flex board and a helmet called the Flyaway. "I made good money off that for a while," he says. "But that only lasted about a year."

"A ROLLING BALL OF CHAOS" In the mid-'70s, Adams and Alva were a step ahead of everyone, pioneers of skating's hardcore approach to life in general. But in the late '70s, the punks caught up. "Black Flag, Circle Jerks, Descendents, Bad Religion, Suicidal Tendencies. We picked up on all the music that was happening in L.A. at that time," says Alva. "There was so much energy at those shows. Skate and punk fed off each other because they were both total outlets for aggression."

Punk replaced Ted Nugent and Jimi Hendrix as the soundtrack for skate sessions; the music paralleled the sessions themselves, which had been turning more and more violent as the Dogtowners' hard-core reputations preceded them. "A lot of people were gunning for us, because they'd read about us in the magazines," Alva says. "We were like a rolling ball of chaos, this mobile gang on a recon mission. We'd show up at a skatepark somewhere, and there'd be guys who'd come up to us and get in our faces, telling us we weren't so hard-core." Naturally, a fight would ensue.

At night, after going to shows for local bands like Suicidal Tendencies (whose lead singer was Jim Muir's younger brother Mike), things got even more violent. "We'd go to parties, take Quaaludes, get in fights with bats and stuff," says Adams.

Drugs and alcohol were starting to exact a toll. Alva's friend Bunker O.D.'d from a combination of sedatives and alcohol, while trying to kick a heroin habit. "We definitely lost soldiers because of drugs," says Alva. "Coke, heroin, downers. People started losing track of what was most important--the skating." Alva was nearly a casualty himself: "I did a lot of coke at that time."

Yet in the early '80s, when bands like Black Flag and the Adolescents were on the ascent, the skateboarding industry was collapsing. Skateparks that had opened just a couple years earlier were already starting to close, unable to obtain insurance or attract enough patrons on a regular basis. The kids who'd taken up the sport in the '70s were growing older and giving it up. Making things worse, America slipped into a recession.

Skateboard sales dropped overnight. Stacy Peralta's signature board, which had once sold more than 5,000 units per month, was now selling only a few hundred. Jim Muir and Wes Humpston lost the Dogtown trademark to their business partners, who promptly went bankrupt.

"Things just blew up," says Alva of his own company at that time. "A lot of the money we'd made in the boom went into products that were short-lived--a full, glitzy fashion line, disco roller-skate boots. Just crazy, wack stuff." Sensing the end of skateboarding as a vocation, he dissolved his partnership with Zehnder and moved back in with his father for a while. Soon, he started taking dental technician courses at a local junior college.

In the most unfortunate incident to punctuate that era, Adams's good luck finally failed to coincide with his bad behavior. By 1982, he had developed a taste for tequila and ruining other people's nights. One evening, a trashed Adams and some punk friends found a pair of gay men walking down the street to yell at. When the men yelled back, Adams started kicking one while a friend punched the other. In a few moments, both pedestrians lay face down on the concrete. Others at the scene soon joined in, kicking the two prone men with their steel-toed boots. By the time they were finished, one of the men was dead. Two days after the incident, Adams was arrested at his apartment and charged with murder, though he insisted he had left the scene by the time the others started kicking the men. He was ultimately convicted of assault, for which he served four months in jail.

"We were young and stupid," says Alva, alluding to that incident and his own episodes of alcohol-fueled violence. "There was shit that went down that I wish we had done differently."

"THEY WERE REVOLUTIONARY" When skateboarding's popularity began to rise again in the mid-'80s, thanks in large part to the trailblazing videos that Stacy Peralta created to promote Powell-Peralta, the Dogtowners were no longer the most technically accomplished skaters. A new wave of kids like Christian Hosoi and Rodney Mullen and Tony Hawk had surpassed them. In the years that have followed, very little about Dogtown has ever made it into any form more permanent then the occasional magazine article-- there are Glen E. Friedman's books of photos, Fuck You Heroes and Fuck You Too, which included numerous photos of Alva, Adams, chapters in Michael Brooke's recently released history of skateboarding, The Concrete Wave.

But if the history of Dogtown is largely forgotten today, its influence is inescapable. "They were revolutionary style-setters," says Kevin Thatcher, publisher of Thrasher. "I mean, snowboarding, rollerboarding, skysurfing, even surfing now-- it all comes from what Jay and Tony were doing 20 years ago. So many people are trying to be hard-core now, but those guys didn't even have to try. It just came to them naturally."

Today, Jay Adams lives and surfs in Hawaii, where he keeps a vintage Zephyr- Flex fiberglass skateboard in the backseat of his car. On the back of his neck, in dark blue ink, a small tattoo reads 100% SKATEBOARDER 4 LIFE. And, despite his brush with dental technology, Tony Alva realized he could never work a regular job. He resurrected his company in the mid-'80s, and continues to produce his namesake boards. For the last 32 years, he's never gone more than a few days without skating some new drainage ditch or backyard pool or multimillion-dollar skatepark.

Which is what he's doing now at the Vans opening. Poised at the edge of the pool, he's watching the kid who dropped in on him, waiting for that flash of miscalculation. And, just before the kid loses it, just before gravity and failed nerve send his board in one direction and him in another, Alva, with a sixth sense developed over three decades of such opportunistic surveillance, drops and begins his run.

Two hours later, as Alva and his girlfriend exit the park's front entrance, they pass some minor disturbance. A group of kids are trying unsuccessfully to argue their way into the park. But Alva and his girlfriend are oblivious to the confrontation. They disappear into the crowd of shoppers, and don't even notice the three policemen responding to the scene.

"Well, what did they expect?" one of the cops is saying as they brush by Alva and his girlfriend. "Of course they're going to have problems. They put a skatepark in the middle of a mall."

******************************