RE:UP

magazine

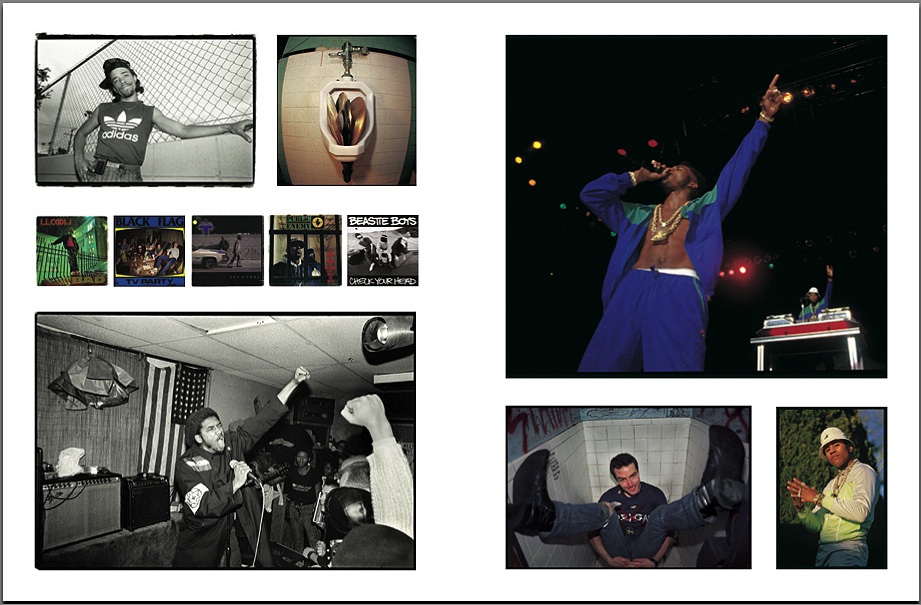

THE PHOTOGRAPHY OF GLEN E. FRIEDMAN

text Peter Agoston“I take being a documentarian as an insult… I’m a part of what I photograph. I’m not someone coming in and stealing from the scene and I feel like a documentarian is someone that is an outsider.”

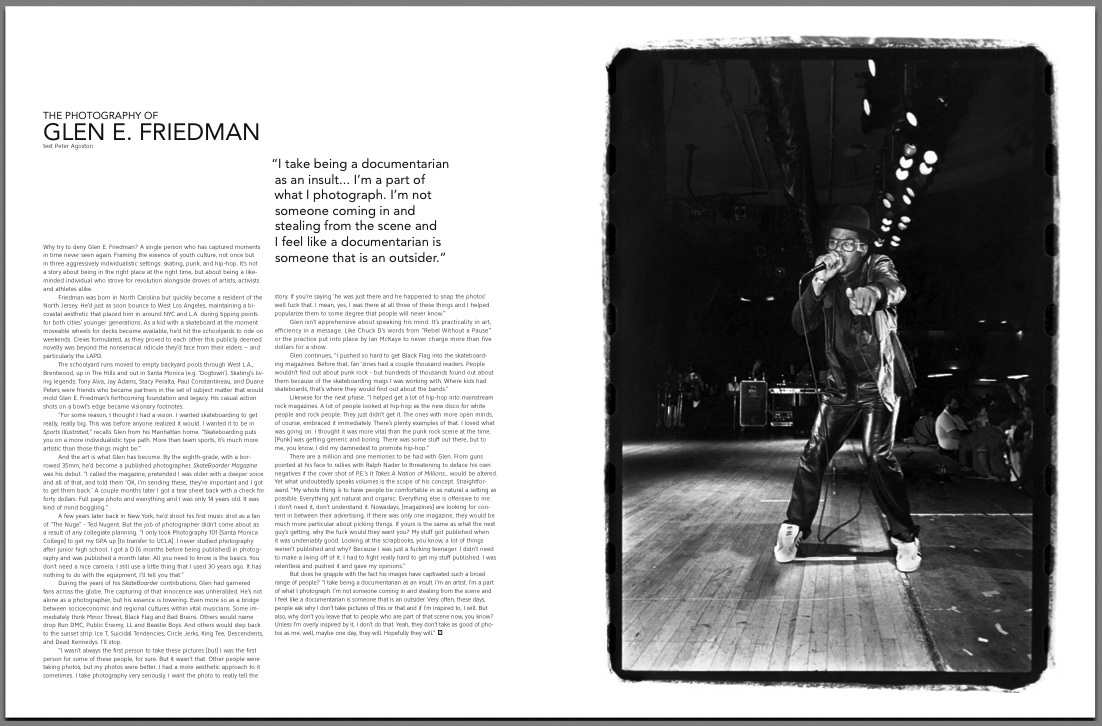

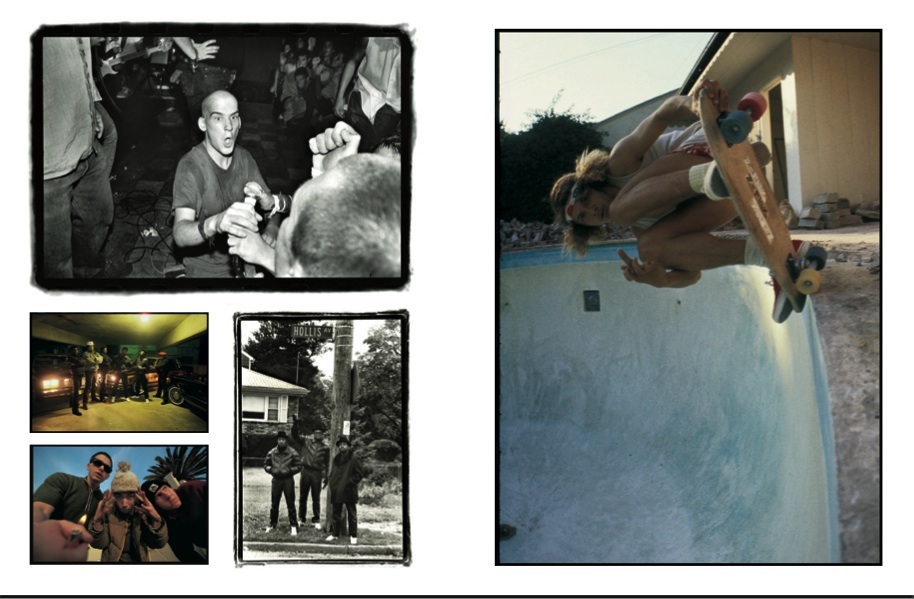

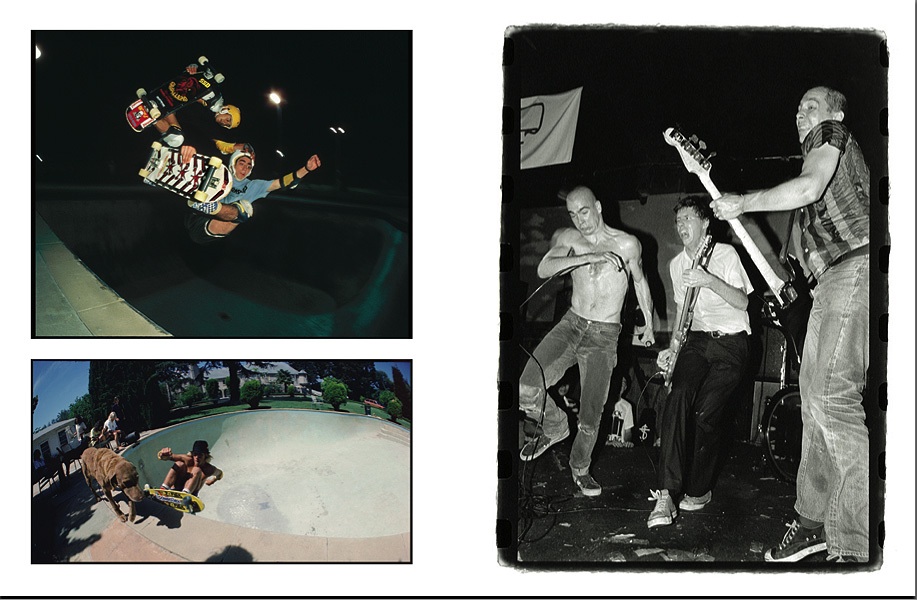

Why try to deny Glen E. Friedman? A single person who has captured moments in time never seen again. Framing the essence of youth culture, not once but in three aggressively individualistic settings: skating, punk, and hip-hop. It’s not a story about being in the right place at the right time, but about being a like- minded individual who strove for revolution alongside droves of artists, activists and athletes alike.

Friedman was born in North Carolina but quickly become a resident of Northern Jersey. He’d just as soon bounce to West Los Angeles, maintaining a bi- coastal aesthetic that placed him in around NYC and L.A. during tipping points for both cities’ younger generations. As a kid with a skateboard at the moment moveable wheels for decks became available, he’d hit the schoolyards to ride on weekends. Crews formulated, as they proved to each other this publicly deemed novelty was beyond the nonsensical ridicule they’d face from their elders – and particularly the LAPD.

The schoolyard runs moved to empty backyard pools through West L.A., Brentwood, up in The Hills and out in Santa Monica (e.g. ‘Dogtown’). Skating’s liv- ing legends: Tony Alva, Jay Adams, Stacy Peralta, Paul Constantineau, and Duane Peters were friends who became partners in the set of subject matter that would mold Glen E. Friedman’s forthcoming foundation and legacy. His casual action shots on a bowl’s edge became visionary footnotes.

“For some reason, I thought I had a vision. I wanted skateboarding to get really, really big. This was before anyone realized it would. I wanted it to be in Sports Illustrated,” recalls Glen from his Manhattan home. “Skateboarding puts you on a more individualistic type path. More than team sports, it’s much more artistic than those things might be.”

And the art is what Glen has become. By the eighth-grade, with a bor- rowed 35mm, he’d become a published photographer. SkateBoarder Magazine was his debut. “I called the magazine, pretended I was older with a deeper voice and all of that, and told them ‘OK, I’m sending these, they’re important and I got to get them back.’ A couple months later I got a tear sheet back with a check for forty dollars. Full page photo and everything and I was only 14 years old. It was kind of mind boggling.”

A few years later back in New York, he’d shoot his first music shot as a fan of “The Nuge” – Ted Nugent. But the job of photographer didn’t come about as a result of any collegiate planning. “I only took Photography 101 [Santa Monica College] to get my GPA up [to transfer to UCLA]. I never studied photography after junior high school. I got a D [6 months before being published] in photog- raphy and was published a month later. All you need to know is the basics. You don’t need a nice camera. I still use a little thing that I used 30 years ago. It has nothing to do with the equipment, I’ll tell you that.”

During the years of his SkateBoarder contributions, Glen had garnered fans across the globe. The capturing of that innocence was unheralded. He’s not alone as a photographer, but his essence is towering. Even more so as a bridge between socioeconomic and regional cultures within vital musicians. Some im- mediately think Minor Threat, Black Flag and Bad Brains. Others would name drop Run DMC, Public Enemy, LL and Beastie Boys. And others would step back to the sunset strip: Ice T, Suicidal Tendencies, Circle Jerks, King Tee, Descendents, and Dead Kennedys. I’ll stop.

“I wasn’t always the first person to take these pictures [but] I was the first person for some of these people, for sure. But it wasn’t that. Other people were taking photos, but my photos were better. I had a more aesthetic approach to it sometimes. I take photography very seriously. I want the photo to really tell the story. If you’re saying ‘he was just there and he happened to snap the photos’ well fuck that. I mean, yes, I was there at all three of these things and I helped popularize them to some degree that people will never know.”

Glen isn’t apprehensive about speaking his mind. It’s practicality in art, efficiency in a message. Like Chuck D’s words from “Rebel Without a Pause” or the practice put into place by Ian McKaye to never charge more than five dollars for a show.

Glen continues, “I pushed so hard to get Black Flag into the skateboard- ing magazines. Before that, fan ‘zines had a couple thousand readers. People wouldn’t find out about punk rock – but hundreds of thousands found out about them because of the skateboarding mags I was working with. Where kids had skateboards, that’s where they would find out about the bands.”

Likewise for the next phase. “I helped get a lot of hip-hop into mainstream rock magazines. A lot of people looked at hip-hop as the new disco for white people and rock people. They just didn’t get it. The ones with more open minds, of course, embraced it immediately. There’s plenty examples of that. I loved what was going on. I thought it was more vital than the punk rock scene at the time. [Punk] was getting generic and boring. There was some stuff out there, but to me, you know, I did my damnedest to promote hip-hop.”

There are a million and one memories to be had with Glen. From guns pointed at his face to rallies with Ralph Nader to threatening to deface his own negatives if the cover shot of P.E.’s It Takes A Nation of Millions… would be altered. Yet what undoubtedly speaks volumes is the scope of his concept. Straightfor- ward. “My whole thing is to have people be comfortable in as natural a setting as possible. Everything just natural and organic. Everything else is offensive to me. I don’t need it, don’t understand it. Nowadays, [magazines] are looking for con- tent in between their advertising. If there was only one magazine, they would be much more particular about picking things. If yours is the same as what the next guy’s getting, why the fuck would they want you? My stuff got published when it was undeniably good. Looking at the scrapbooks, you know, a lot of things weren’t published and why? Because I was just a fucking teenager. I didn’t need to make a living off of it. I had to fight really hard to get my stuff published. I was relentless and pushed it and gave my opinions.”

But does he grapple with the fact his images have captivated such a broad range of people? “I take being a documentarian as an insult. I’m an artist. I’m a part of what I photograph. I’m not someone coming in and stealing from the scene and I feel like a documentarian is someone that is an outsider. Very often, these days, people ask why I don’t take pictures of this or that and if I’m inspired to, I will. But also, why don’t you leave that to people who are part of that scene now, you know? Unless I’m overly inspired by it, I don’t do that. Yeah, they don’t take as good of pho- tos as me, well, maybe one day, they will. Hopefully they will.”