SWINDLE

First Annual Icons Issue

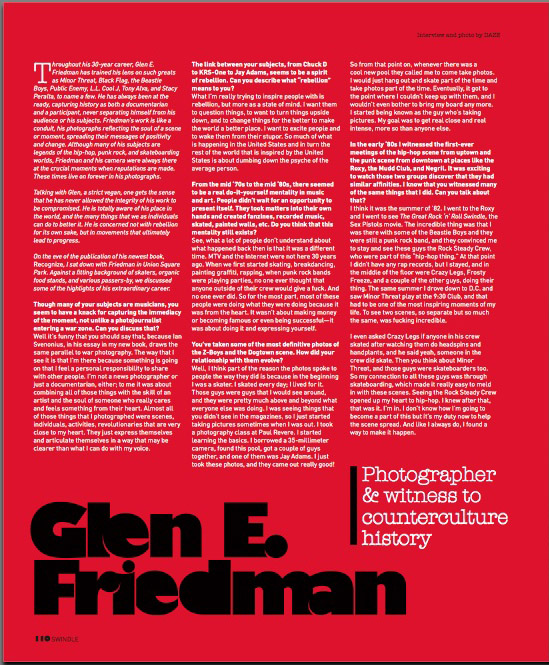

Interview and photo by DAZEGlen E. Friedman

Photographer & witness to counterculture history

Throughout his 30-year career, Glen E. Friedman has trained his lens on such greats as Minor Threat, Black Flag, the Beastie Boys, Public Enemy, L.L. Cool J, Tony Alva, and Stacy Peralta, to name a few. He has always been at the ready, capturing history as both a documentarian and a participant, never separating himself from his audience or his subjects. Friedman’s work is like a conduit, his photographs reflecting the soul of a scene or moment, spreading their messages of positivity and change. Although many of his subjects are legends of the hip-hop, punk rock, and skateboarding worlds, Friedman and his camera were always there at the crucial moments when reputations are made. These times live on forever in his photographs. Talking with Glen, a strict vegan, one gets the sense that he has never allowed the integrity of his work to be compromised. He is totally aware of his place in the world, and the many things that we as individuals can do to better it. He is concerned not with rebellion for its own sake, but in movements that ultimately lead to progress.

On the eve of the publication of his newest book, Recognize, I sat down with Friedman in Union Square Park. Against a fitting background of skaters, organic food stands, and various passers-by, we discussed some of the highlights of his extraordinary career.

Though many of your subjects are musicians, you seem to have a knack for capturing the immediacy of the moment, not unlike a photojournalist entering a war zone. Can you discuss that?

Well it’s funny that you should say that, because Ian Svenonius, in his essay in my new book, draws the same parallel to war photography. The way that I see it is that I’m there because something is going on that I feel a personal responsibility to share with other people. I’m not a news photographer or just a documentarian, either; to me it was about combining all of those things with the skill of an artist and the soul of someone who really cares and feels something from their heart. Almost all of those things that I photographed were scenes, individuals, activities, revolutionaries that are very close to my heart. They just express themselves and articulate themselves in a way that may be clearer than what I can do with my voice.

The link between your subjects, from Chuck D to KRS-One to Jay Adams, seems to be a spirit of rebellion. Can you describe what “rebellion” means to you?

What I’m really trying to inspire people with is rebellion, but more as a state of mind. I want them to question things, to want to turn things upside down, and to change things for the better to make the world a better place. I want to excite people and to wake them from their stupor. So much of what is happening in the United States and in turn the rest of the world that is inspired by the United States is about dumbing down the psyche of the average person.

From the mid ‘70s to the mid ‘80s, there seemed to be a real do-it-yourself mentality in music and art. People didn’t wait for an opportunity to present itself. They took matters into their own hands and created fanzines, recorded music, skated, painted walls, etc. Do you think that this mentality still exists?

See, what a lot of people don’t understand about what happened back then is that it was a different time. MTV and the Internet were not here 30 years ago. When we first started skating, breakdancing, painting graffiti, rapping, when punk rock bands were playing parties, no one ever thought that anyone outside of their crew would give a fuck. And no one ever did. So for the most part, most of these people were doing what they were doing because it was from the heart. It wasn’t about making money or becoming famous or even being successful—it was about doing it and expressing yourself.

You’ve taken some of the most definitive photos of the Z-Boys and the Dogtown scene. How did your relationship with them evolve?

Well, I think part of the reason the photos spoke to people the way they did is because in the beginning I was a skater. I skated every day; I lived for it. Those guys were guys that I would see around, and they were pretty much above and beyond what everyone else was doing. I was seeing things that you didn’t see in the magazines, so I just started taking pictures sometimes when I was out. I took a photography class at Paul Revere. I started learning the basics. I borrowed a 35-millimeter camera, found this pool, got a couple of guys together, and one of them was Jay Adams. I just took these photos, and they came out really good! So from that point on, whenever there was a cool new pool they called me to come take photos. I would just hang out and skate part of the time and take photos part of the time. Eventually, it got to the point where I couldn’t keep up with them, and I wouldn’t even bother to bring my board any more. I started being known as the guy who’s taking pictures. My goal was to get real close and real intense, more so than anyone else.

In the early ‘80s I witnessed the first-ever meetings of the hip-hop scene from uptown and the punk scene from downtown at places like the Roxy, the Mudd Club, and Negril. It was exciting to watch those two groups discover that they had similar affinities. I know that you witnessed many of the same things that I did. Can you talk about that?

I think it was the summer of ’82. I went to the Roxy and I went to see The Great Rock ‘n’ Roll Swindle, the Sex Pistols movie. The incredible thing was that I was there with some of the Beastie Boys and they were still a punk rock band, and they convinced me to stay and see these guys the Rock Steady Crew, who were part of this “hip-hop thing.” At that point I didn’t have any rap records, but I stayed, and in the middle of the floor were Crazy Legs, Frosty Freeze, and a couple of the other guys, doing their thing. The same summer I drove down to D.C. and saw Minor Threat play at the 9:30 Club, and that had to be one of the most inspiring moments of my life. To see two scenes, so separate but so much the same, was fucking incredible.

I even asked Crazy Legs if anyone in his crew skated after watching them do headspins and handplants, and he said yeah, someone in the crew did skate. Then you think about Minor Threat, and those guys were skateboarders too. So my connection to all these guys was through skateboarding, which made it really easy to meld in with these scenes. Seeing the Rock Steady Crew opened up my heart to hip-hop. I knew after that, that was it. I’m in. I don’t know how I’m going to become a part of this but it’s my duty now to help the scene spread. And like I always do, I found a way to make it happen.