STAF magazine (Spain)

GLEN E. FRIEDMAN interview (Spanish & English)

23 October 2014 Texto: David Moreu. Fotografía: Glen E. Friedman. excepto “*”.

Foto portada: Jay Adams en el Dog Bowl, Santa Monica, California. 1977.

YOU KNOW WHEN YOU ARE RIGHT: STORIES BEHIND THE CAMERA

Una de las grandes paradojas sobre los mitos de la cultura pop es si el recuerdo de ciertas manifestaciones artísticas o sociales se debe a lo que vivimos en estricto directo o a la representación fotográfica que ha perdurado en el imaginario colectivo con el paso de los años. ¿Sería tan radical el mundo del patín sin el vértigo que desprenden las fotos de los Z-Boys en los años 70? ¿Sería tan salvaje el legado del punk norteamericano sin las fotos movidas de los conciertos de Black Flag y Fugazi en la década de los 80? ¿Habrían llegado al número uno de las listas de ventas los Beastie Boys y Run-DMC sin esas campañas promocionales con fotos que rompían la frontera entre lo alternativo y lo mainstream? Seguramente no hay una única respuesta correcta a tantos dilemas existenciales, pero lo que está claro es que nada de esto habría sucedido sin la pasión y la mirada vanguardista de un fotógrafo como Glen E. Friedman. Muchas veces se dice que la suerte de esta profesión consiste en estar en el lugar adecuado y en el momento oportuno, pero resulta que este icono de la cámara vivía permanentemente en el ojo del huracán y logró retratar estas escenas desde dentro, como un protagonista más de lo que sucedía a su alrededor. No en vano, es amigo de los pioneros del skate de Dogtown, estaba en el backstage en los garitos donde nació el hardcore y se codeaba con Rick Rubin en los inicios del sello Def Jam. Puede que ahora la carrera de Glen E. Friedman haya quedado suspendida en el limbo, pero acaba de presentar un libro titulado “My Rules” en el que revisa su extensa carrera y nos abre las puertas de su archivo personal. Hemos tenido la oportunidad de entrevistarlo para descubrir qué se escondía detrás de su objetivo y cómo vivió aquellos momentos de cambio en los que la cultura alternativa reinó por encima de todo lo demás.

Allan “Ollie” Gelfand, Florida 1979.

Empecemos por el inicio de esta aventura: ¿podrías contarnos de dónde eres y cómo llegaste a California siendo un adolescente?

Nací en Carolina del Norte mientras mi padre estaba en el ejército durante un año y entonces regresamos al sitio donde vivíamos, que se llamaba Englewood y estaba en New Jersey. Estuve allí hasta que me trasladé a California en segundo o tercer curso del colegio con mi madre, eso fue alrededor de 1970. Mis padres se divorciaron en aquella época y apenas recuerdo vivir con ellos juntos. Yo era un niño y me trasladé con mi madre, pero mi padre se quedó en la zona de New York, muy cerca de Manhattan, y siempre lo visitaba cuando tenía vacaciones del colegio.

En varias ocasiones has comentado que en tu vida primero fue el skate y después vino la fotografía. ¿Cómo era la escena del patín en aquella época’?

Sólo tenía 9 o 10 años cuando llegué a California, así que el skate todavía no era tan relevante. Lo más curioso es que me di cuenta de que los chavales eran mucho más libres allí y que no pasaban demasiado tiempo junto a sus padres. Me di cuenta de que fumaban, de que tenían relaciones con el sexo opuesto mucho más pronto y de que estaban más avanzados en ese sentido. Por el contrario, no eran demasiado buenos en el colegio e iban más lentos. Fue un cambio interesante y coincidió que al llegar allí me compraron un skate. Supongo que era algo que los críos hacían habitualmente, como un juego o un juguete que utilizabas de vez en cuando, parecido a la bici. Recuerdo que era un patín rojo que ahora puedes encontrar en eBay. Pero, poco tiempo después, aparecieron las Cadillac Wheels y en 1974 salieron las ruedas blandas y todo empezó a evolucionar. Dejó de ser un juguete y los chavales ya empezaban a ir por la ciudad, bajaban por pendientes o patinaban en los patios de los colegios. Se convirtió en un hobby para ocupar tu tiempo libre y nos aficionamos.

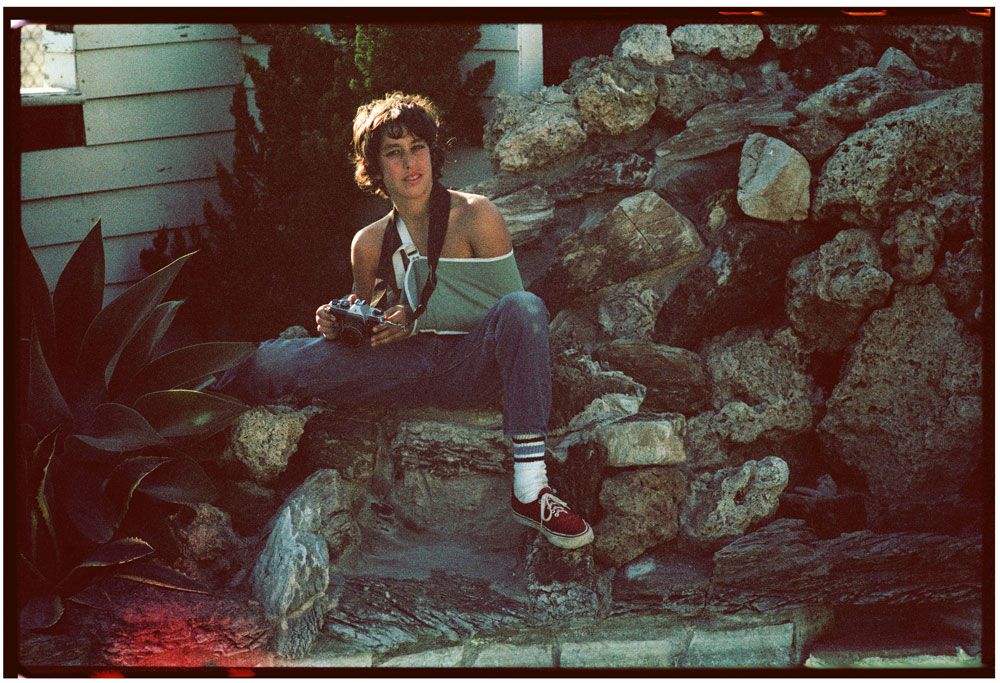

Glen E. Friedman por Hugh Holland (*)

¿En qué momento decidiste coger una cámara y empezar a hacer fotos?

Yo me pasaba el día patinando y llegó un momento en el que pensé que la gente con la que iba y lo que hacíamos era extraordinario. Estaba convencido de que algo increíble estaba sucediendo y recuerdo que ya había una revista sobre skate. Algunos de los tíos que conocía aparecían en sus páginas y a otros nunca se lo habían propuesto, aunque hacían cosas más asombrosas y se lo merecían más. Yo estaba en el epicentro de todo eso y decidí empezar a hacer fotos de manera muy rudimentaria con una cámara compacta de plástico. No utilizaba carrete de 35 mm, sino que se conocía como una cámara de formato 110 con una película muy pequeña. Y así empecé porque no tenía nada más a mi alcance. Lo bueno es que podía guardarla en mi mochila y nadie quería robármela. No tenía que preocuparme por nada. Básicamente, empecé a hacer fotos mientras patinaba, aunque después me apunté a clases y aprendí a revelar mis propios negativos y a imprimir mis imágenes. Sin embargo, lo más importante fue que aprendí los conceptos básicos y eso no tiene precio. Me familiaricé con los tipos de ópticas, de películas, la apertura, la profundidad de campo, el foco… a pesar de que no podía hacer nada de eso con mi cámara porque solamente tenía un foco. Entonces no creía que la calidad fuera tan importante, hasta que me di cuenta de que estaba equivocado. Resulta que hacía fotos muy buenas, pero no podían utilizarlas ni retocarlas porque la calidad no era suficientemente buena, no como la de una cámara de 35 mm con su óptica correspondiente.

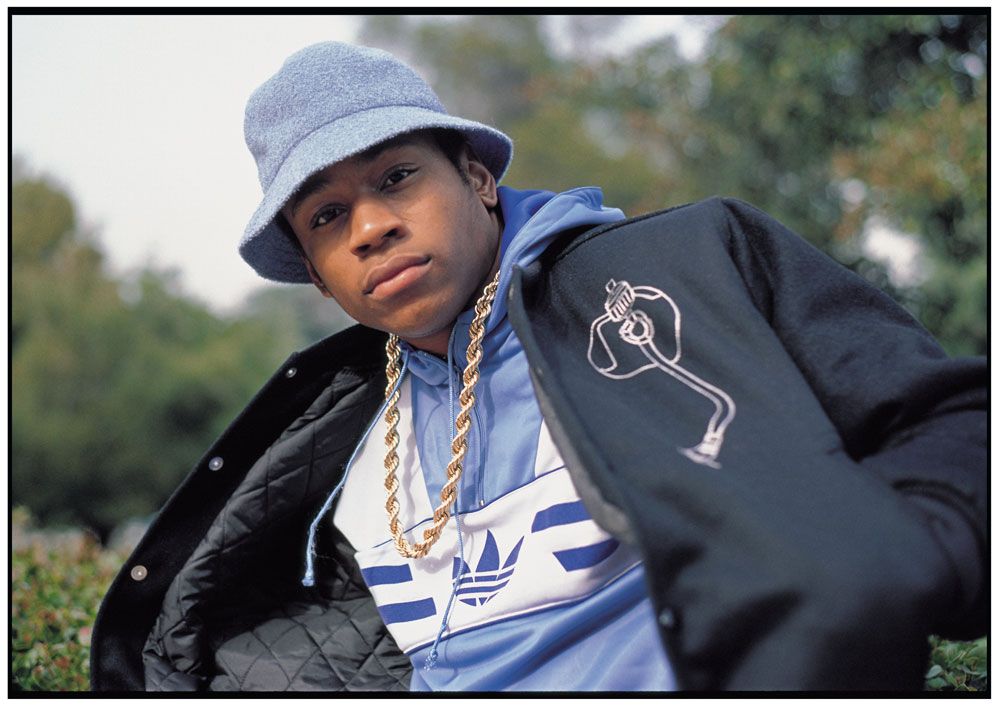

LL Cool J en1986 en el campus universitario de la Universidad de Los Angeles: UCLA

¿Recuerdas la primera vez que publicaste una foto en una revista?

Un día encontré esa piscina vacía y pensé que sería un momento muy especial para mí porque era un descubrimiento mío y, además, podría hacer las fotos que quisiera. Sabía que todo eso que sucedía a mi alrededor interesaba a la gente, así que pedí prestada una cámara y disparé un carrete de 35 mm en color y otro en blanco y negro. Y logré que me publicaran una de esas fotos… entonces tenía 14 años.

Después de leer tu nuevo libro, queda claro que tu carrera puede resumirse en cuatro capítulos muy diferenciados. El primero nos lleva a los años 70 durante la revolución del skate. ¿Cómo conociste realmente a los Z-Boys?

Mi conexión con los Z-Boys empezó porque patinábamos en los mismos sitios. Yo no era un surfista como ellos, pero me crié en esa cultura. Por el hecho de venir de la Costa Este, me sentía un poco como un outsider porque no había crecido en California. Eso era obvio porque tenía el pelo negro rizado y no rubio y liso como la mayoría. Tampoco me gustaba levantarme pronto por la mañana para ir a coger olas como los surfistas. Y tampoco tenía un hermano mayor que me llevara a la playa con la tabla de surf. Nunca me aficioné a ese deporte, pero sí que viví su cultura y siempre acababa bajando a la playa hacia la tarde. Entonces el skate también formaba parte de la cultura de playa. Lo que sucedió es que todos nosotros patinábamos en los dos patios de los colegios más populares y yo iba a ambos, así que conocía a esos tíos de manera cercana. Mucho más que la gente que venían desde Venice o desde Santa Mónica. Me refiero a que yo vivía allí y ellos venía expresamente a patinar a esa zona. Así fue como conocí a los Z-Boys porque simplemente éramos chavales que patinaban y se sentaban en los bancos y hablaban de la gente. Entonces empecé a hacerles fotos, pensaron que eran buenas y nos hicimos grandes amigos.

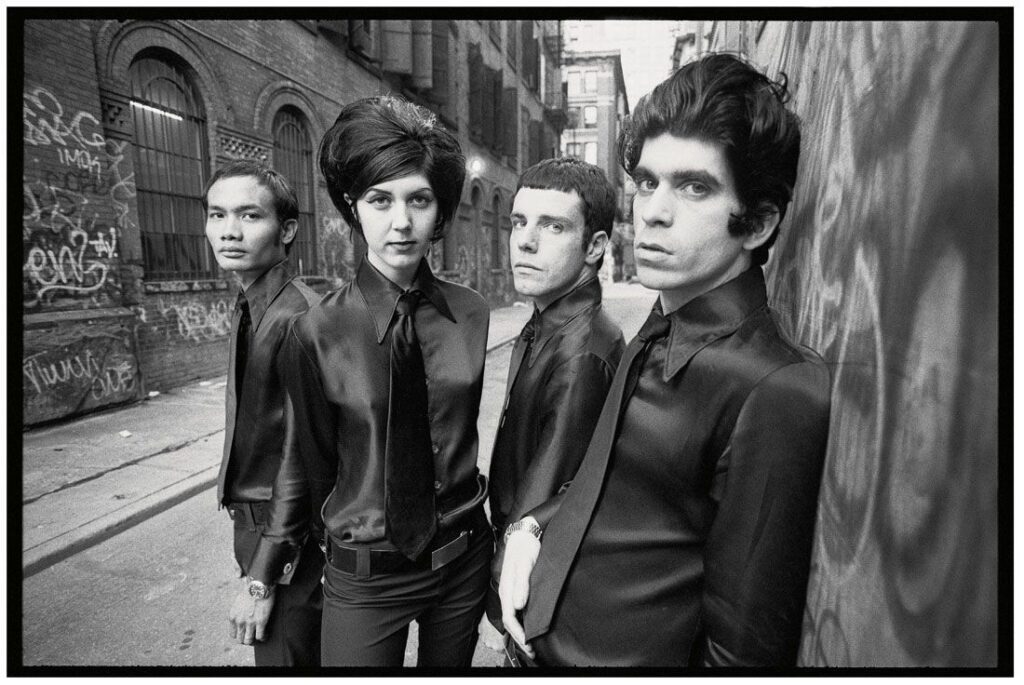

The Make-Up, New York City 1995

Las sesiones clandestinas en piscinas vacías se han convertido en leyenda, pero tengo entendido que todo empezó gracias a la sequía estival…

Realmente no había ninguna sequía, sino que pusieron restricciones en el consumo de agua, pero los chavales ya patinaban igualmente en las piscinas. Lo que sucedió fue que resultó aún más sencillo cuando las autoridades dijeron a la gente que no podían llenarlas en verano. Y cada vez había más gente con el skate porque cada vez había más piscinas vacías. Luego hubo algunos que se atrevieron a vacíar sus propias piscinas o que iban por la calle buscando piscinas para vaciarlas cuando los propietarios de la casa estuvieran de vacaciones. Incluso nos metimos en casas que aún se estaban construyendo o en casas de gente que tenían la piscina vacía y sabías que no había nadie, aunque debías vigilar para ver cuando regresaban.

El segundo capítulo de tu carrera ocurre en la década de los 80 con la explosión del hardcore. ¿Cómo te involucraste en aquella escena musical? ¿Estaba conectada con el mundo del patín?

Me gusta hablar de música punk en lugar de hardcore porque, según mi parecer, eso no es un estilo de música. La música que más tarde pasó a llamarse hardcore era muy genérica y no tenía interés para mí, ¿sabes a qué me refiero? No era excitante. Me gusta el punk porque amo la música y en los años 70 también escuchábamos a Jimi Hendrix, Led Zeppelin o incluso Aerosmith. Puede que aún no fuéramos tan originales como para escuchar a The Stooges, pero nos encantaba el rock n’ roll y entonces el punk se presentó como una alternativa excitante, agresiva, rápida y ruidosa. Era algo nuevo, así que empezamos a escucharlo y algunos skaters montaron sus propias bandas. Supongo que estaban aburridos y empezaron a tocar música porque eso les parecía más emociónate. Entonces no había skaters profesionales que llegaran a los 20 años, todos eran adolescentes… solamente había unos cinco pros que superaran los 20 años. En aquellos días todos tenían un trabajo normal, hacían otras cosas con su tiempo y los pros aún no ganaban demasiado dinero con el skate.

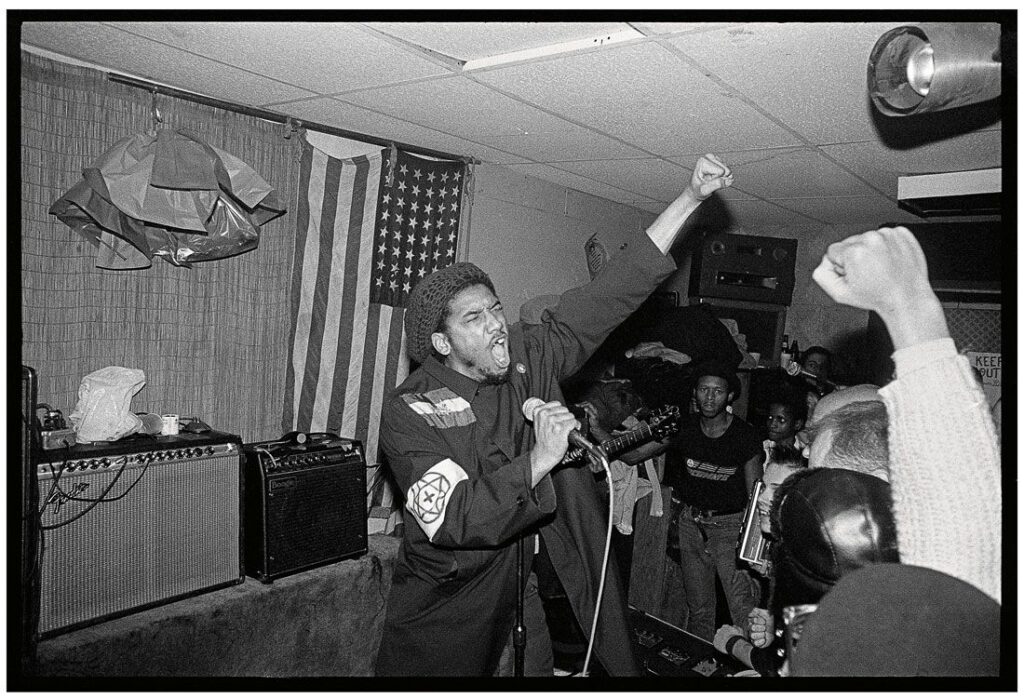

HR de Bad Brains, New York City 1982.

Dos de las bandas que más fotografiaste fueron Black Flag y Fugazi. ¿Qué era lo que más te atraía de aquel movimiento social y musical?

Lo que más me gustaba de los conciertos de punk era que siempre tenía acceso a la banda. Estaba muy cerca de ellos. Era la primera vez que podía sentarme en el escenario y hacer fotos. Eso era mucho más excitante que cualquier otra cosa que hubiera visto jamás. En el período de tiempo que aprendí a hacer fotos de skate, descubrí la importancia de captar el momento correcto y eso me ha ayudado durante toda mi vida profesional. No en vano, el skate es algo que se mueve muy deprisa, pero captar el ambiente donde sucede la acción también es muy importante para reflejar lo que sucede. De este modo aprendes a componer las imágenes. Entonces me resultó muy sencillo hacer fotos de conciertos porque me salía de manera natural. Era un entusiasta tan grande de la música, que solamente quería compartir esas instantáneas con otra gente. Conocía algunos miembros de las bandas gracias a la revista Skateboarder, así que no tardamos en hacernos amigos. Quería difundir su música y que más gente los conociera, así que era muy feliz haciendo esas fotos. Aunque la mayoría de veces que iba a ver conciertos no hacía fotos porque la luz en los locales era muy pobre. Recuerdo que conocí a Fugazi gracias a Minor Threat y a estos los conocí a través de The Faith… resulta que una vez fui a un concierto donde actuaban Bad Brains y The Faith, y me presentaron a Ian. Sabía que a esos tíos les gustaban mis imágenes de skate, así que acabamos siendo buenos amigos. Son gente muy simpática e Ian acabó siendo uno de mis mejores amigos. Por supuesto, cuando montaron Fugazi, yo estaba allí desde el principio. Ellos me inspiraron mucho con su música y yo sólo intenté difundirla.

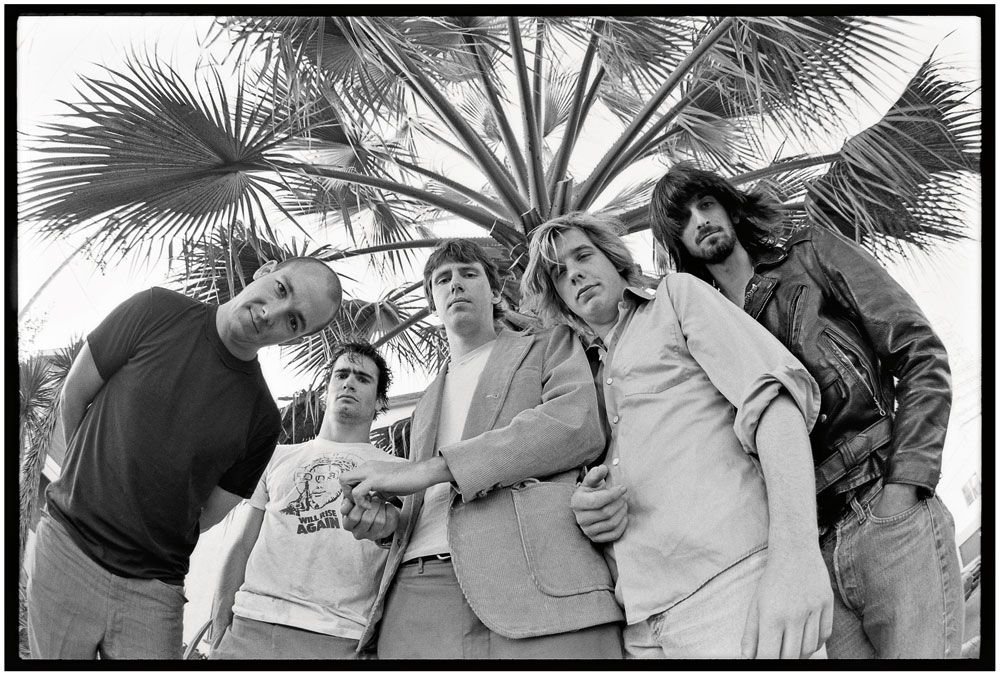

Black Flag, 1982

Una de las anécdotas más curiosas que aparecen en tu libro es cuando Rick Rubin afirma que te encargó la sesión de fotos de los Beastie Boys después de ver tus imágenes para Black Flag…

Eso no es cierto, simplemente es cómo él lo recuerda. Conocí a los Beastie Boys cuando todavía eran una banda de punk y hablé con ellos cuando me enteré de que habían grabado un disco de rap. Resulta que querían que les hiciera unas fotos siguiendo el estilo de los paparazzi, con estrellas de cine y mucha gente a su alrededor… ¡realmente querían era que les consiguiera hacer una foto con Madonna! Eso fue lo que me pidieron, el resto fue todo idea mía porque su música me inspiraba. Honestamente, eso no tiene nada que ver con alguien pidiéndome esas fotos como un encargo.

¿Crees que el punk y el hip hop estaban conectados de alguna manera?

Todo estaba relacionado gracias a la actitud, a la energía y, sobre todo, porque entonces era algo que no estaba controlado por ninguna gran empresa o por gente adulta. Se trataba de gente joven que nos llevó a lugares que los mayores no podían entender, predecir o incluso controlar. Eso fue lo que hizo de esos movimientos algo único y especial.

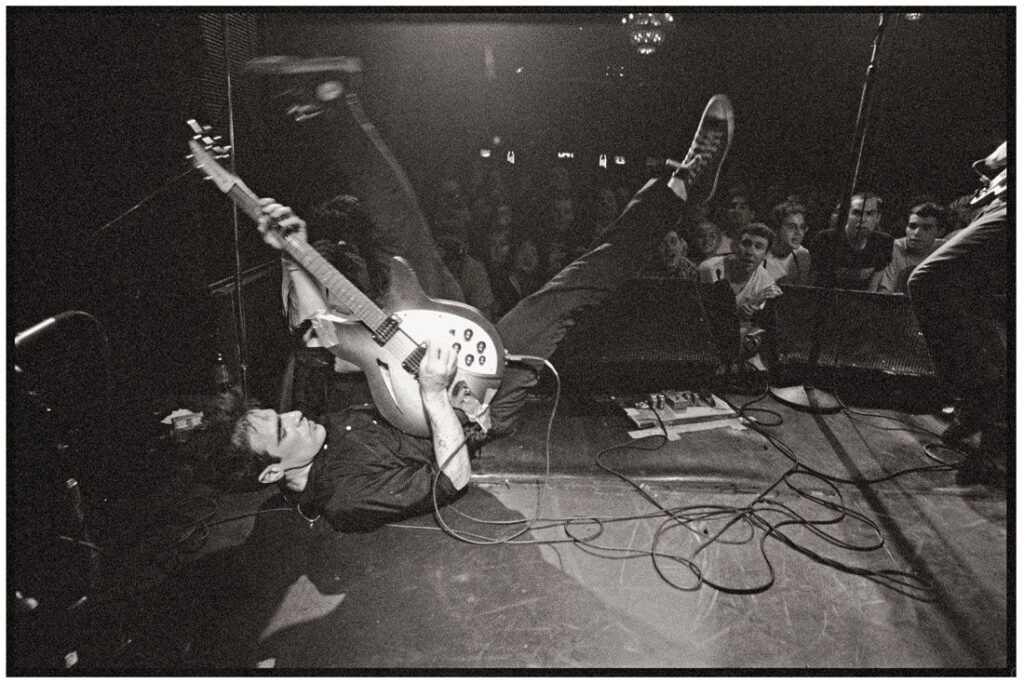

Guy Picciotto de Fugazi, New York City, 1994

En aquellos días lograste que tus fotos aparecieran en las portadas de álbumes y de singles muy exitosos como “Walk This Way” de Run-DMC, “Check Your Head” de los Beastie Boys y “It Takes a Nation of Millions…” de Public Enemy. ¿Participabas también en el proceso de diseño y de maquetación?

La mayoría de veces hacía fotos porque me encantaban los grupos y quería contribuir a difundir su música. Resulta que yo tenía esas imágenes y las discográficas se ponían en contacto conmigo bastante tiempo después, preguntándome si podían usarlas en sus portadas de discos porque a las bandas les encantaban. Normalmente los sellos no estaban cómodos trabajando conmigo porque yo quiero controlarlo todo: no recurro a un director de arte y lo hago todo yo mismo. Y a las discográficas les gusta controlar todo el proceso por su cuenta.

El tercer capítulo de esta aventura nos lleva a principios de los años 90, cuando la cultura alternativa se volvió mainstream. ¿Cuándo te diste cuenta de que el skate y la música estaban creciendo demasiado?

En los años 90 hubo algunas bandas como Jane’s Addiction y los Red Hot Chili Peppers que no me llamaban la atención. Eran grupos de Los Ángeles, pero siempre tuvieron el sueño de firmar con multinacionales. Es cierto que había buenos músicos, sin embargo, actuaban como si fueran estrellas de rock. No me involucré con ellos porque eran de otra generación. Si habías visto a los Bad Brains, a Black Flag y a Minor Threat, resultaba difícil que te gustaran esas otras bandas, incluso si habías crecido con los Ramones y los Buzzcocks. Eran bandas geniales para los años 90, pero no me impresionaron, así que nunca las fotografié.

Sesion de piscina en la zona Oeste de Los Angeles (California), en 1978

El cuarto y último capítulo se está viviendo en estricto presente y corresponde a las manifestaciones sociales en las calles, puesto que tú participaste en el Occupy Wall Street. ¿Cómo lo viviste desde dentro?

Todo lo que he hecho a lo largo de mi carrera ha tenido una motivación política, pero lo que sucede es que como ahora ya no hago tantas fotos de skate ni de música, es más fácil apreciar la parte politizada. Sin embargo, es algo que forma parte de mi vida. Incluso antes de aficionarme al skate, ya era un crío con motivaciones políticas. Lo que ha ocurrido en los últimos años es que la gente ha salido a la calle con los puños alzados y ha iniciado esta batalla para salvar sus países y el mundo. El problema es que todavía existe un estado militarizado en la mayoría de países alrededor del mundo y son tan fuertes que resulta muy complicado enfrentarte a ellos, hacerte escuchar o incluso protestar porque te ponen detrás de esas barreras. Es algo brutal e intimidan a la gente para que no quieran cambiar las cosas. Lo más curioso es que esos policías no trabajan para el gobierno, sino que protegen a las empresas. Las corporaciones deberían preocuparse más por la gente y no sólo por sus beneficios. Es por este motivo que nos oponemos a toda esta mierda en una época tan dura. Raramente hago fotos en las manifestaciones, creo que ya hay otros allí para hacerlo. No siento la necesidad ni la urgencia de coger mi cámara en esos momentos.

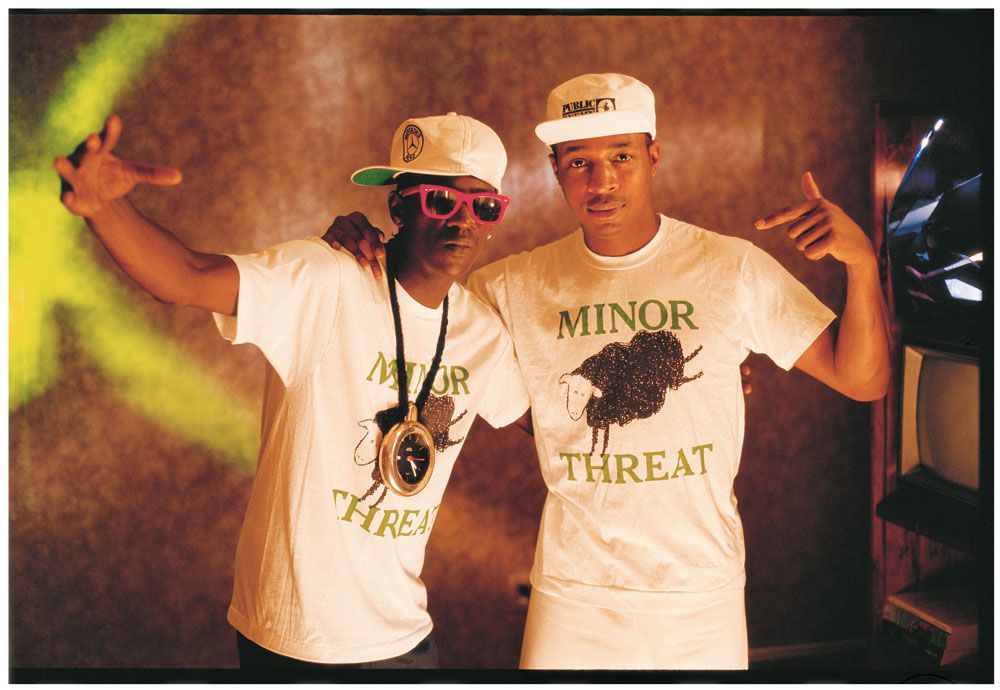

Flavor & Chuck D. Public Enemy, 1988

¿Qué puedes avanzarnos sobre tus proyectos de futuro y qué te gusta hacer cuando no llevas una cámara en la mano?

Me encanta hacer fotos, pero no me gusta llevar la cámara a todos lados. Nunca me ha gustado. Ahora hago fotos de vez en cuando, tengo un hijo de siete años y cada dos meses le saco fotos… y utilizo carretes de verdad, no cámaras digitales. También hice unas fotos a las Pussy Riot en New York y ésas fueron las últimas fotos que incluí en el libro. Solamente fotografío a bandas y skaters si creo que debo hacerlo. Podría hacerlo cada día y conseguir imágenes muy buenas, pero no me apetece. Sólo quiero vivir mi vida y hacer fotos no lo es todo.

Antes de terminar la entrevista me gustaría preguntarte sobre el recientemente fallecido Jay Adams. ¿Cómo describirías su figura como amigo y pionero del skate?

Jay y yo éramos amigos desde que éramos muy jóvenes. En cierto modo, empezamos juntos en este mundo de la cultura underground y nos convertimos en gente conocida. Yo hice algunas de sus fotos más populares e incluso la primera imagen que publiqué era suya. Jay era un año mayor que yo y eso que él era el más joven de los Z-Boys. Teníamos una gran conexión e hicimos muchas locuras juntos cuando éramos críos. No salíamos juntos siempre porque él no era mi mejor amigo, pero eso no quita que estuviera jodidamente loco. ¡No podías estar con el y no meterte en problemas! Hablamos mucho durante los años, me mandaba cartas desde la prisión y, de vez en cuando, me llamaba para saber cómo estaba. Una vez fui a Hawai, pero no logramos encontrarnos. No lo vi en 25 años y eso que publiqué un libro sobre él titulado “Jay-Boy” con la ayuda de su padre. Jay era una caja de sorpresas porque era salvaje, pero también tenía otra faceta más profunda y reflexionaba mucho sobre las cosas.

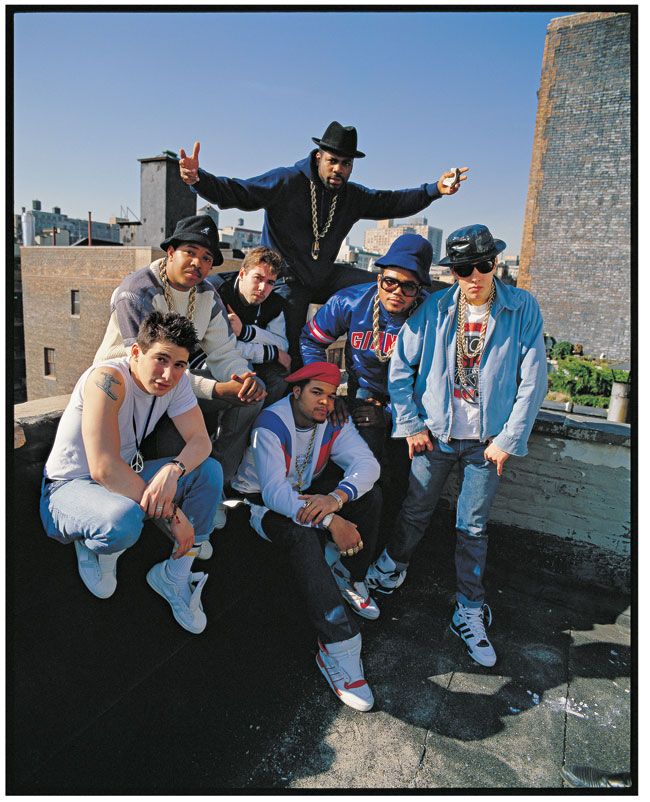

Run-DMC y Beastie Boys, New York City, 1988

Para más información: www.burningflags.com

Glen E. Friedman

You know when you are right: stories behind the camera

One of the greatest paradoxes about pop culture is the fact that we don’t know whether our memories of certain art or social forms come from our direct experience or the photographic representation that has endured in the collective imagination throughout the years. Would the skateboard world be so radical without the hustle and bustle that the Z-Boys photographs of the 70s portray? Would the legacy of North American punk be so wild without the fuzzy pictures of Black Flag and Fugazi concerts in the 80s? Would the Beastie Boys and Run-DMC have reached the number 1 on the charts without those promotional campaigns with those photographs that tore down the borders between the alternative and the mainstream scenes? Probably there isn’t an exact answer to all those dilemmas. But what’s obvious is that nothing would have happened without the passion and the ground-breaking look of a photographer like Glen E. Friedman. It is often said that in order to have luck in this profession you have to be in the right place at the right time, but as it turns out this photography icon lived permanently in the eye of the hurricane and managed to portray those scenes from the inside, as a witness of what happened around him. And of course he’s a friend of the DogTown pioneers, he was in the backstage of the clubs where hardcore punk was born and he rubbed shoulders with Rick Rubin in the beginnings of the Def Jam record label. It might seem like Glen E. Friedman’s career is now suspended. But he just released a book named “My Rules”, in which he looks over his extensive career and takes us into his personal archive. We had the chance to interview him and find out what’s hidden behind his lens and how he lived those moments of change in which the alternative culture prevailed over anything else.

Let’s start from the beginning of this adventure: where are you from and what is your family background?

I was born in North Carolina, while my father was in the Army there for a year, and then I moved back up to where he lived, which was in Englewood (New Jersey). So I lived there until I moved to California in second or third grade with my mom, it was around 1970. My parents got divorced then and I don’t even remember them living together. I was a little kid and I moved with my mom, but my dad stayed here in the New York area, actually, very close to Manhattan, and every long school holiday I would come back to visit with him.

You said that you started to skateboard before grabbing a camera. How was that scene in those early days?

I was only 9 or 10 years old, so it wasn’t that big a deal. What was interesting was that I did realize the kids were much more freer in California; they were not around their parents as much. I noticed kids were smoking and making out at much younger ages, you know, with the opposite sex and they were more advanced in that way. Even though they also weren’t as smart in school, they were much slower. So, it was a very interesting change. But also when I moved to California I got a skateboard. I guess it was something kids did. It was just a way to play, almost like a toy that you used sometimes, like riding a bicycle or something like that. I got the skateboard very early and it was a red Makaha that you can find around on eBay these days. But then, Cadillac Wheels (the soft wheels) came out four years later, around 1974. That is when it really changed. It wasn’t just a toy anymore and kids were just cruising around a little bit, it became more of a hobby or an activity that you really did, riding in the streets and down big hills or at school yards. That became something to do and something to occupy your time and something that you concentrated on.

When did you decide starting taking pictures?

I was riding and eventually I thought what I was doing and the people I was hanging out with were extraordinary. I thought something incredible was going on and there was a magazine out at that time about skateboarding. And I thought some of the guys I knew were in the magazine and others were not, but I thought they should be there because they were doing things that were cooler than the people in the magazine. So, I was in the epicentre of what was going on and I decided to start taking pictures in a very rudimentary way with an “instamatic” camera, which was made of plastic for the most part. It wasn’t a 35 mm; it was called a 110 camera with a very tiny film. And I started shooting those pictures because that is what I had. I could put it in my pocket and no one really wanted to steal it. It wasn’t something much to worry about. So, I started taking pictures while I was skating sometimes. Then I took a photography class and I started developing and making my own prints, but I also learned all the basics, which I think is invaluable. I learned all about lenses and about films, about aperture, about depth of field, focus… even though my camera couldn’t adjust any of those things because there was just one focus. That was it, you know. I didn’t think the quality was that important back then, until I realized it was necessary in order to get published. I realized I was taking some really cool pictures and they couldn’t really publish them because the quality was not good enough, because I wasn’t using a 35 mm camera with its lenses and ability to sharp focus.

Do you remember the first time you got a photo published in a magazine?

OF COURSE. One day, eventually, I found this pool and I thought it would be a very special moment for me because I found it and I knew I could take pictures. I knew I was around things that were going on that people wanted to see. So, what I did was… I borrowed a real camera from somebody in the neighborhood, and I shot one roll of colour and one roll of black and white 35 mm film, and then from that day I got a photo published. I was 14 years old. It was incredible.

After reading your new book, it seems that there are four main chapters in your career. The first one brings us back to the 70’s during the skateboard revolution. How did you become friends with the Z-Boys?

My connection with the Z-Boys was that we just skated the same embanked school yards. I wasn’t a surfer, but I grew up in surf culture. Coming from the East Coast, I felt a little bit as an outsider, you know, because I didn’t grow up in California. It was obvious. I had dark curly hair, not blonde straight hair, and I didn’t like waking up early in the morning like surfers had to do. And I didn’t have an older brother to take me to the beach surfing. And I never got into it, but I lived within that culture and I would go to the beach later on the day. I would ride my skateboard and that was all a part of beach culture back then. I lived in between the two most prominent schoolyards for skating and I went to both schools, so I knew them intimately, much more so than the people who came from other parts of town to skate. I mean, I lived there and they just came to skate. So that is how I got to meet the Zephyr team riders, just kids hanging out on the banks, and talking people and seeing people. And then I started taking pictures and people thought they were good…

Those swimming-pool invasions have become legend, but it was because the summer drought…

There was a drought, they had shortage of water, but people were skating pools anyway. It just became really easy at that time when people were told that they couldn’t refill their swimming pools. So, people started skating pools more and more because there were more empty pools. People started emptying their own pools or more often finding pools and emptying them when the house owners were on holidays and knew they weren’t around. Or they found places that were under construction and emptied those, or even better, abandoned houses.

The second chapter in your career starts in the 80’s, with the explosion of hardcore Punk music. How did you get involved in that scene? Was it connected to skateboarding in some way?

I like punk music because I love music; I also listened to Jimi Hendrix, Led Zeppelin or even Aerosmith in the 70’s. Maybe we weren’t cool enough to know about The Stooges yet, but we listened to rock n’ roll and punk seemed a like a new, exciting, enthusiastic and aggressive, fast and loud music. And it was younger, so we started listing to that and some of the skaters started bands. They got bored and started playing music because it seemed more exciting than anything else going on at the time. Back then, no pro skaters were in their 20’s, they were all teenagers. There were like five pros, that were around 20 years old. You had a normal job, did other things and pro skateboarders didn’t make much money anyway.

The main bands that you photographed were Black Flag and Fugazi. What did you enjoy about that music and scene?

Well those were my favorite bands that had lasting impact.The thing that was really great about punk shows is that you had access to the band. You were really close to the live show action. It was the first time I was able to sit on the stage and take pictures; that was way more exciting than anything else I had seen. With the timing I developed shooting skateboarding, I had a sense of the right moment and that helped my photography for my whole life. Because skateboarding is something that moves very quickly, but also the environment is very important to what is going on. So, you learn how to compose images well if you are a skateboard photographer. And with music it was just very easy and natural for me. And because I was so enthusiastic about the music, I wanted to share it with other people. I knew some people from the bands because of my association with SkateBoarder magazine, so that is how I got to meet a lot of people involved and become friends. I wanted to help popularize what was going on; I wanted more people to know about this vital music, so I was happy to shoot photos. With some of these bands I was there from the beginning. And they inspired me with what they did. I just tried to spread the word.

I really enjoyed reading in your book the text by Rick Rubin. Your black Flag photo is what got you the session for the Beasties Boys…

That is not true, that is how he remembers it. I met the Beastie Boys when they were a punk band and I reached out to them when I heard they made up a rap record. And they wanted me to shoot pictures of them, like paparazzi stuff with movie stars and people around during the Madonna tour… they really wanted me to get a picture of them with Madonna for press. That was all they asked me for, everything else I did on my own because they inspired me. And it has nothing to do with anyone else asking me to do it, quite honestly.

Do you think punk music and hip-hop were connected in some way?

It was all connected by attitude, by its energy and because it was not controlled by corporations or adults for the most part. They were very young people who took us to places where older people could never predict, understand or even control. That was what made those special and unique, all those activities.

In those days you had your first photos on record covers, such as “Walk This Way” by Run-DMC, “Check Your Head” by The Beastie Boys and “It Takes a Nation of Millions…” by Public Enemy. Where you also involved with the designing process?

Very often I shoot pictures because I am inspired by the groups and I want to help spread their inspiration. So, I would have these great photos and then the record companies would come to me afterwards and ask if they could use the photos because the bands liked them. Record companies, generally, didn’t like me because I control everything: I don’t ever use an art director, I just do it all myself. And record companies like to control all the processes.

The third chapter in your career brings us to the early 90’s, when alternative culture became mainstream. When did you notice for the first time that things were changing and getting bigger in skateboarding and music?

When people started selling more records and the influence of the earlier progressive cultures were being copied and becoming more generic and less creative… it was a weird time, still is. Except of course there are some great exceptions, few and far between, but those “Golden Ages” were very special, nothing like it since.

The fourth and final chapter is still happening with today’s social revolutions in the streets because you also have been involved in the Occupy Wall Street movement as an individual. How was it from inside? Did you take any photos of those demonstrations?

Everything has always been political motivated. There has always been a politic in everything. It just so happens that I am not shooting skateboard and music as much, so now you happen to see a little bit of the politics more, but it has always been in my life. Even before skateboarding, I was a politically motivated child. What has been happening the last few years is that people have been getting up in arms and starting this battle for the country and for the world. The problem is the military state that exists in most countries around the planet now, they are so strong that it is really hard to fight back and be heard or even to argue and to protest because they put you behind barriers. It is so brutal that they intimidate people from changing. It’s really unfortunate because most of these policeman don’t work for the peoples’ governments, they are protecting corporations. Corporations have to learn to care about humans, not only their profits. That is why people are raising against this bullshit in a really tough time. I hardly ever take pictures of demonstrations; other people might be there to take pictures. I don’t feel the urgency to take them. I’m there to make some fucking noise!

What are your current projects as a photographer and what do you enjoy doing when not carrying a camera?

I love taking pictures, but I don’t like carrying a camera. I never had. Now I take pictures very rarely, I have a 7-year-old son that I shoot film photographs of every 2 months. I use actual film as opposed to digital. You know, I shot pictures now and then. I shot pictures of Pussy Riot last year, the very last photos to go in the new book. I only take pictures of people if I think they need to be done. I could do it all the time and shoot great pictures every day, but I don’t want to. I just want live my life and taking photos is not all of it.

Before finishing the interview, I would like to ask you about your relationship with the late Jay Adams. How was he like as a friend and as a pioneer skateboarder?

Jay Adams and I were friends since we were very young and, in many ways, we started together in this world of underground culture and becoming known. I shot some of his most popular photographs; even my first published photo was of him. He was a year older than me and he was the youngest of the Z-Boys. We had a strong connection and did a lot of crazy things together when we were kids. We didn’t hang out all the time, he wasn’t my best friend, but he was fucking wild. You couldn’t hang out with him all the time without getting into trouble! Over the years we always talked, he sent me letters when he was in jail sometimes, and called me every once in a while, just to check in. I even made a book with him, about him as a kid before i knew him, with his step-father called “Jay-Boy.” Jay was always a surprise, because he was wild, but there was another side of him where he was very deep and thinking about things. He was a living legend… and a crazy friend… now he’s gone, we have the memories and for you all who didn’t know him personally, i am happy we have the photos to share. I suspect his legend will live on gloriously.

www.burningflags.com